The atypical method of reproduction may aid in the rapid spread of invasive yellow crazy ants.

According to a report published in the April 7 issue of Science, yellow crazy ants (Anoplolepis gracilipes) defy the conventional rules of reproduction. Researchers have discovered that every male aint contains two distinct genetic lineages, which makes them "chimeras." This unique method of reproduction is exclusive to yellow crazy ants, making them the only known species to require chimerism to create fertile males.

Evolutionary geneticist Waring "Buck" Trible from Harvard University, who was not part of the study, describes this as an "elegant response to the kinds of unusual mating systems we've observed in other ants," and suggests that it could be the next evolutionary step for ants.

In most animals, development occurs when a sperm cell and an egg cell combine and merge their DNA, resulting in subsequent cells carrying two sets of DNA-bearing chromosomes, one from each parent, except for sex cells, which carry only one set of chromosomes.

However, many ants, as well as wasps and bees, have a different method of development. In these species, only females possess somatic cells with chromosome pairs, whereas males typically develop from unfertilized eggs, resulting in their somatic cells only carrying one set of chromosomes.

In 2007, a study discovered that approximately half of the male yellow crazy ants examined had two identical copies of the same genes, similar to female worker ants in the species. However, according to evolutionary biologist Hugo Darras from Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany, it was not logical for all males in the species to be diploid, with two sets of chromosomes in each somatic cell, since this typically results in male sterility in other ant species. The reason for this phenomenon remained unknown.

To unravel this mystery, Darras and his team collected hundreds of yellow crazy ants from East and Southeast Asia. They analyzed queens and workers to determine the genetic source of royalty in this species. They found that reproductive queens were produced by combining sperm and egg cells from the same lineage, which the researchers named R. Meanwhile, workers were hybrids of two different lineages, including R and W, resulting in them having R/W genomes, while queens had R/R genomes.

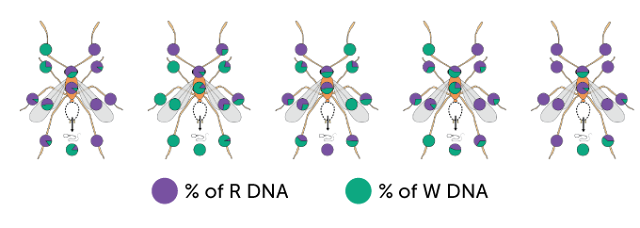

The recent study confirmed the previous findings of R/W males. However, the researchers also discovered that the somatic cells of male yellow crazy ants carry only one set of chromosomes, similar to other ant species. The DNA analysis conducted on individual cells revealed that each cell contained chromosomes from only one of the two lineages, rather than chromosome pairs within cells.

Further experiments showed that the distribution of R and W cells within the males' bodies was uneven. Although the majority of the body contained R cells, accounting for nearly 75 percent of the sampled tissue, the ratio was nearly reversed in the sperm, with 65 percent being W cells.

The reason behind the evolution of this unique mode of reproduction in yellow crazy ants remains unclear. However, it is believed that the sperm might be able to increase its reproductive output by refusing to fuse with the egg cell. This is because female worker ants are sterile and cannot pass on the W genome. According to Darras, this unusual reproductive method could be an interaction between two genomes that are in conflict but sometimes cooperate.

It is possible that these distinct lineages evolved independently in two separate ant populations that eventually intermingled. Alternatively, they may have started with similar genes that diverged over time, but it appears that the whole genomes are separated and do not exchange any genetic material.

Indeed, this discovery raises many questions about the possible presence of similar systems in other ant species, and it opens up new avenues for research in ant genetics and reproduction. Understanding the mechanisms behind the yellow crazy ant's unique reproduction system could also have implications for understanding the evolution of reproductive strategies in other organisms.

CITATIONS

H. Darras et al. Obligate chimerism in male yellow crazy ants. Science. Vol. 380, April 7, 2023, p. 55. doi: 10.1126/science.adf0419.

J. Drescher, N. Blüthgen and H. Feldhaar. Population structure and intraspecific aggression in the invasive ant species Anoplolepis gracilipes in Malaysian Borneo. Molecular Ecology. Vol. 16, April 2007, p. 1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03260.x.