Neurons in the gut lining of mice are linked to the production of mucus, which may help to maintain a healthy microbiome.

|

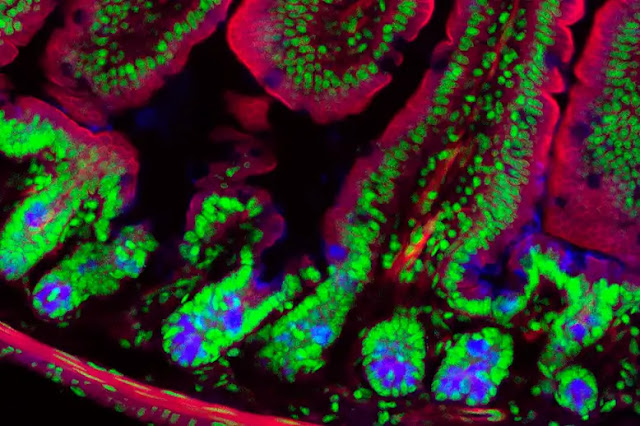

| Pain that affects the lining of the mouse's gut may have some protective properties. Kevin Mackenzie/ABERDEEN UNIVERSITY/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY |

Neurons in the gastrointestinal lining of mice that transmit pain signals may help to maintain a healthy gut microbiome.

Harvard University's Isaac Chiu and colleagues wanted to learn more about the role of pain neurons in the gut. "When you look for pain fibers in the gut, you usually find them near epithelial cells [which cover the gut lining], which suggests that they can communicate," says Chiu.

To begin, the researchers genetically modified mice to have no pain neurons in their gut lining.

Without these neurons, the mice had thinner layers of mucus lining their guts than non-genetically modified rodents.

The modified mice also had a significantly different microbiome than the unmodified mice, indicating that thicker mucus aids in the maintenance of a healthy microbial community.

"These findings suggest that pain is critical for maintaining the integrity of our mucus layer as well as the health of our microbiome," says Chiu.

For a variety of reasons, pain that affects the gut lining may be linked to mucus production. "Some potentially harmful products in the GI [gastrointestinal] tract, such as salmonella or E. coli, may necessitate immediate attention," he says. "You may want to coat the gut with mucus to protect it, and mucus may even aid in wound healing, though this is speculative."

In a second part of the experiment, the researchers genetically sequenced several of the mucus-producing cells. They discovered that these goblet cells have receptors on their surface that bind to a chemical produced by neurons, specifically the neuropeptide CGRP.

"It suggests that pain fibers that produce CGRP may be communicating with goblet cells via this transmitter," says Chiu.

The researchers then discovered that activating pain neurons in the gut lining of mice resulted in goblet cells producing mucus within minutes.

In a laboratory experiment, the researchers examined human goblet cells and discovered that they, too, express high levels of the CGRP receptor. "We believe that human goblet cells may respond to the same molecule from pain fibers," Chiu says.

Many migraine medications, according to Chiu, inhibit CGRP signaling. CGRP is expressed in both nervous systems of the body: the central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system, which is made up of nerves that branch off from the spinal cord and extend to all other parts of the body.

"These drugs may have a negative effect if they cause the mucus lining of the gut to be thinner in people and the microbiome in the gut to be dysregulated," says Chiu.

According to Chiu, the interaction between pain neurons and cells in the gut lining may be involved in the discomfort felt by many people with ulcerative colitis, an inflammatory bowel disease.

"This elegant study highlights yet another line of communication that has co-evolved between the intestinal microbiota and the mammalian host," Imperial College London's Jon Swann says.

"This gives the host a mechanism to maintain gut homeostasis and protection during intestinal inflammation, and the microbes influence mucus secretion, which is a major factor in gut health."

Journal reference: Cell, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.024