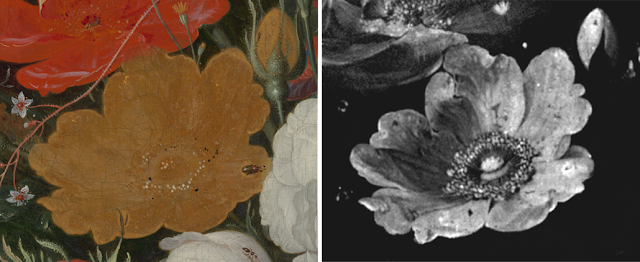

The decay of an arsenic-based paint removed the shadows and light from a still life flower.

.jpg) |

| In Abraham Mignon's otherwise lively painting Still Life with Flowers and a Watch, a flat, lifeless yellow rose stands out. DUPPER WIN. BEQUEST, DORDRECHT |

The fading of a once-vibrant yellow rose demonstrates how time and chemical alteration can diminish a painting's visual power.

The majority of the flowers in Abraham Mignon's 17th-century painting Still Life with Flowers and a Watch appear to leap from the canvas. One yellow rose, however, is a flat, jarring element, painted with arsenic sulfide-based orpiment pigment. That was not Mignon's intention: the rose's luster was lost due to the chemical transformation of some of its original bright pigment into colorless lead arsenates, according to a study published in Science Advances on June 8.

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam's painting conservator Nouchka De Keyser and colleagues examined the rose using noninvasive techniques such as X-ray fluorescence imaging and X-ray powder diffraction (SN: 10/1/21). The team first traced the traces of arsenic, lead, calcium, and other chemical elements in the paint layers to reveal how Mignon carefully layered paint to create a nearly three-dimensional rose out of light and shadow.

The analyses also revealed the presence of two newer crystals on the rose that contained both lead and arsenic. The crystals, known as mimetite and schultenite, are the result of a series of chemical reactions. First, the reaction of orpiment with light produced arsenolite, a highly mobile type of arsenic. The mobilized arsenolite then found its way to an underlying layer of lead white paint, where it chemically reacted with it to form mimetite and schultenite. The crystals are colorless and flatten the appearance of the flower because they lack the bright color of the orpiment.

Science cannot reverse the chemical transformation to restore the rose's former glory — it is a one-way street. However, digital reconstructions made using similar techniques as in the new study could provide several benefits to people other than scientists and art historians, according to De Keyser. Such reconstructions can not only reveal now-faded elements in other paintings, but they may also appear in museums, giving visitors a ghostly glimpse of a painting's true past.

Reference :

N. De Keyser et al. Reviving degraded colors of yellow flowers in 17th century still life paintings with macro-and microscale chemical imaging. Science Advances. Published online June 8, 2022. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abm2106.